This originally posted on NJWV.

The main photography show at the new SFMOMA is on California and the West and how they have had an integral role in the development of the art form. It’s good but is more of a primer, introducing the different photographic “schools” that have developed here. In other words, it’s a bit thin and I wish it had gone deeper.

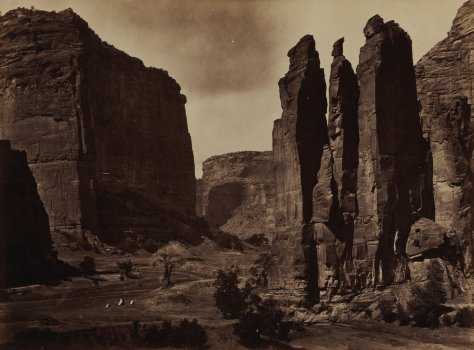

The main issue is that it sort of waffles between being organized thematically versus being ordered chronologically. The wall text suggests that things are chronological but the actual photos for a supposed time period end up covering over a century. This is most obvious in the Early Landscapes room. It feels like it’s about the 19th century Watkins, Russell, Muybridge, and O’Sullivan school of mammoth plates, albumen prints, pristine spectacular western landscapes, and our early attempts at taming them. But it goes into Ansel Adams work from ~50 years later and even includes a Friedlander photo from 2004.

In many ways the exhibition would’ve been better off just making the rooms purely thematic—similar to Oakland’s Inspiration Points show a couple years ago. This is pretty much how I chose to approach the show after the first couple of rooms. By focusing on the themes and ignoring the chronology cues, I found myself thinking about how each theme could cover ~150 years of photography in the West.

Early Landscapes was intended to set up a transition to the New West.* These photographs are very much my thing. I love Baltz and Robert Adams. Henry Wessel’s photo of the Richmond garage tree is fantastic.** It’s always nice to see Shore prints.

*I’m tempted to start calling the pristine landscapes either “Old West” or “Old Topographics” a retronyms to either The New West or The New Topographics.

**And I’m completely unable to find it online anywhere.

The comparison between these views of The West is one which I feel deeply in my own photography. I very much love going out into nature and hiking with my camera. I also love going out into the suburban sprawl and taking photos of—and criticizing—the cityscape that has resulted. They’re more than just a core part of my visual literacy, they’re home.

I also like the older landscape photography because of how its message differs from landscape photography today. Modern landscape photography is often environmental-minded, relying on the glory of unspoiled nature to remind the viewer that nature needs to be preserved. 150 years ago, the message was almost the opposite. The glory of unspoiled nature was all potential and something we could, and should, tame.

While the Old West is distinct from the New West, the New West is visible in many of the Old West photos. “Photographing the incursion of technology into nature” is one of photography’s original subjects. Watkins and Robert Adams may have had different goals with their photography, but we can see as many similarities in their work as we can see between Watkins and Ansel Adams.

I found it interesting that the conflict and chaos theme—really more about demographic change—only started with photos from the 1960s. Muybridge photographed the Modoc War 100 years prior.* Dorothea Lange has photographs from the Great Depression in the adjoining room. The history of California is a history of conflict and demographic change, it’s not something which started in the 60s.

*Also an exhibition at the California Historical Society which I need to see this summer.

I do however enjoy seeing how photographers address the social issues of their time. Where political comment is often absent from the rest of the modern art canon,* photography has always been on the front lines. As much as there’s disagreement about what the democratic camera means, it’s pretty clear that as an art form, photography is somewhat unique in how it’s accessible to many more people and has always had an element of not just witnessing, but being part of any conflicts.

*In the rest of the museum, it’s only visible in the Anselm Keifer and Gerhard Richter rooms. But for the rest of the art from the 1960s and 1970s? If there were politics in it it’s long been scrubbed from the wall texts.

It’s not just conflicts either. A lot of the changes are long-term gradual things which may not even depict changes but rather illustrate existing inequality. These images though, by Jim Goldberg or Carrie Mae Weems, get short shrift in this exhibition. Goldberg’s Rich and Poor is hung on both sides of a hallway—which makes no sense for a series which encourages both close inspection and zig-zagging between images. Weems’s From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried meanwhile is one of those photo series which needs to be seen in its entirety yet only two of the images are on display.

That economic and racial inequality are the two big issues for this year’s election, I can’t help but sort of side-eye the way both of them are minimized here.

Speaking of Lange and social justice, while I approve of featuring the “founders/ƒ.64” as being an important theme of western photography, keeping so much of their work outside of the themes in the rest of the rooms felt strange. The group wasn’t about content but rather technique. Their photos fit with all the other themes in the exhibition. There are pristine landscapes, technological changes, and demographic conflicts on display here, but the exercise in tying them into the other rooms is left to the viewer.

As an ƒ.64 room though I liked that they stayed away from most of the super-iconic photos. There’s Lange’s road. And a few of the Weston images are very familiar. But this room could have been full of just photographs I’ve seen over and over again.* I enjoy just absorbing more of their other work.

*Note, there should probably be such a room at SFMOMA because many of those ƒ.64 photos are extremely important to both photography and the idea that photography is art and all of them are inherently part of the Bay Area’s role in art history.

The last theme involves photographers playing with the medium itself. I’ve been on record saying that I consider Weston to be part of this group but most of these photos are much more recent. As such, many of them don’t quite do it for me.* The ones that do though I really like. In particular, Larry Sultan using day laborers as models and the weird ethical questions they create in the resulting photos. Did they know what they were getting in to? What does it mean to stage photos of gente day laborers using those day laborers as models? I don’t have good answers here either but I enjoy thinking about the questions.

*Contemporary Art is still being sorted by Sturgeon’s Law.

I also loved Klea McKenna’s photograms. And it’s always nice to see Trevor Paglen on display although putting him in the playing-with-the-medium room risks reducing a lot of his work to being about technique rather than interrogating the inherent nature of photography as being surveillance.

Looking at the recent photos though provides a clear example of how art photography has embraced the “make it fucking large” ethos of the collector-driven market. So many of the prints are not just huge, but possibly too big to the point that they feel like they’re only trying to be appreciated for their size rather than as images to be looked at. I understand why this is the case* but I don’t have to like the results.

*They have to compete with paintings and other media in a “bigger is better” arms race in the art-collector world rather than focusing on just photography collectors.

So yeah. I like many of the individual photos but was kind of unsold on the larger theme of the exhibition. As with the opening shows in the rest of the museum, this felt very much like a for-the-masses sketch of possibilities for future shows while staking a claim on a lot of territory.