This previously posted on NJWV.

Every year there’s disagreement about the winner of the World Press Photo of the Year. This is to be expected given the nature of contests but in recent years the discussions have consistently trended toward issues of manipulation and honesty within the ethics of what Photojournalism™ allows. While I’ve touched on this territory in the past* the hyper-prescriptive nature of what kinds of digital manipulation are allowable is not something I’m interested in.

*Nothing in-depth but a quick look through the archives finds a post from 2012 and one from 2014.

This year though the discussion has become one of context and how the image exists in the world—a much more interesting thread to think about. Instead of a discussion about whether the image itself is worthy—it’s as clear a case of unmanipulated professional perfection in imagemaking as I’ve ever seen—the head of the jury has suggested that we need to consider more than just the technical quality of the image in anointing it “the best.”

Unlike the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand in Sarajevo in 1914, the crime had limited political consequences. Placing the photograph on this high pedestal is an invitation to those contemplating such staged spectaculars: it reaffirms the compact between martyrdom and publicity.

I both agree and disagree with what he’s saying. I do however deeply respect that he’s pushing the discussion of imagemaking in that direction. And I think that what he’s saying is more of a discussion about how the media uses images and reports on news than it is about photography itself.

The media has fallen into the “if it bleeds it leads” trap of picking the news based on what has the most salacious details. A graphic photo definitely helps here and I totally buy the argument that this assassination wouldn’t have been news in The West if the photos weren’t any good.

At the same time, I’m uncomfortable with so-easily dismissing this event as being of “little political consequence.” Assassinating an ambassador is a big deal. It’s an attack on The State. As much as I think the Benghazi stuff has been over emphasized in the US, I also don’t think that it should’ve been swept under the rug and forgotten instead. And I’d expect Russia to take it similarly as well.

That we haven’t heard anything about the political consequences of this image isn’t a failure of the image but a failure of the press which reported on a fantastic photo rather than any of the context which allows us to understand the events surrounding the image.

It’s exactly this absence of context which makes it easy for us to worry about the photo becoming a “platform for martyrdom and publicity.” We see the viral fame of the image itself and recognize the messages which can be attached to it. That the most-compelling component of the photo is the shooter, his passion, and his eerie professionalism is especially concerning. We don’t know who he is or what he really stands for but we’re open to hearing his message now.

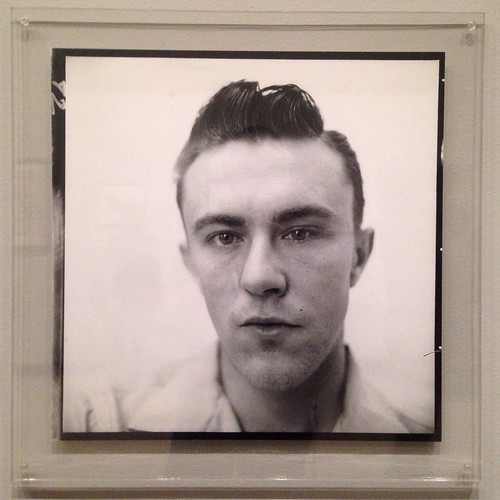

This is in stark contrast to the other World Press Photo of the Year winners which depict assassinations. In Eddie Adams’s photo, the victim is the most compelling figure and we find ourselves wondering who he is instead of the shooter. We know he’s Vietcong and supposedly an enemy. But seeing him at the moment of death forces us to see his humanity.

Meanwhile in Yasushi Nagao’s photo both the killer and the victim are prominent and, while we want to learn more about the event in general, there is something to the look of shock/pain in the victim’s face which sticks with me. Again, his humanity is on display in a way which is very unlike in Özbilici’s photo where you have really look to notice the worn soles on the victim’s shoes.

In neither case is the image so explicitly about the killer. We see and empathize with the victims and, as such, don’t offer the same kind of platform to their killers.

The power of Adams’s image is that while, as Americans, we were supposedly on the same team as the killer, it forced us to reevaluate who our teammates are and the value of what we were fighting for. That it’s part of the narrative of an unpopular war and came out in the midst of an incredible year full of social upheaval only enhanced its power. That, as an American, I totally understand the context in which this photo is working in is a key reason why it’s iconic now. But I also recognize that this is American history on display.

Nagao’s photo on the other hand, while it’s the first image I thought of when I saw Özbilici’s, is still one about which I have no understanding of the larger political context. The image, and the idea that political violence can occur at any political event, has stuck with me ever since I saw it. I’m sure it resonates more strongly in Japan but for me it remains an example of how the media has always lead with compelling images and left the context out.

Anyway, I’m totally here for this discussion and thinking about how photos work as part of the news. And I’m happy to see that there’s a willingness to discuss what our responsibility when publishing photos should be. All very good signs considering how much our media has failed us in the past year.