Note: This originally posted, in a slightly different form, on NJWV.

I love seeing museum exhibitions where photography, paintings, sculpture, etc. are in the same room, in conversation with each other. I can probably count on one hand the number of times I’ve actually seen this. Which means I’m always on the lookout to post anything which can do this.

My last museum trip of the summer was to the Oakland Museum. This was partly to get my Fenton’s fix but I was also interested in the Inspiration Points exhibition since it promised to mix photography, painting, and drawing in the galleries. One of my continuing interests with photography is how it can get out of the photography wing and be exhibited alongside, and in conversation with, other artworks. This doesn’t happen often* so I like to keep an eye out for those cases where it does and go see the show with an eye for how the show itself guides the conversation.

*Why I was so excited by SFMOMA’s Flesh and Metal. And the Jay DeFeo exhibition before that.

The Oakland museum show is a little bit of a mixed bag here. It breaks the concept of California Landscape Art into distinct views and themes, some of which end up being heavily biased toward specific media. So no conversations in those room although there is food for thought about why some themes may be tougher for certain media to handle.

Since each theme ends up being somewhat distinct in character, it makes sense to go through the themes. First, the themes which resulted in galleries which were mixed media.

Mystic

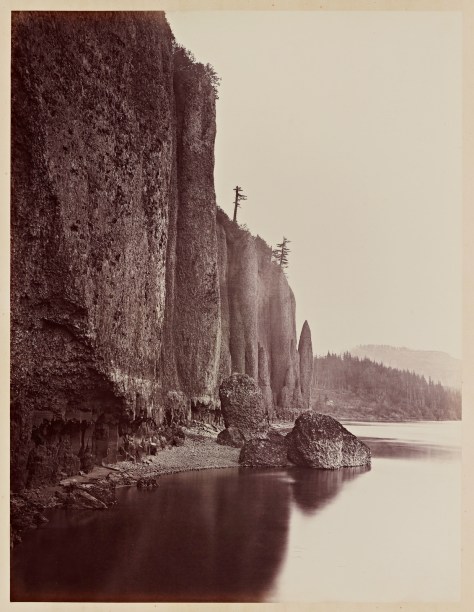

While being mixed between paintings and photography, a lot of the works in this gallery were heavily biased toward pictorialism—or the paintings that those photos were trying to evoke. This isn’t a complaint as it’s quite nice to see those two concepts mixed together so we can actually see how they inform each other.

At the same time, it feels like a somewhat limited take on what mysticism can mean as it biases more toward early-20th-century concepts of myths and the “unspoiled” land in the west rather than looking at the different ways people have developed the landscape for spiritual reasons over the past century.

Exploitation

This theme is of course the flip side of the mystic landscapes. How California is full of natural resources for us to use or conquer is the real state mythology. Documenting the land as we impose out will on it is something everyone—from artists to corporations*— does here. In this case, the method of documentation doesn’t really matter. I don’t get the sense that these works are in conversation although it is interesting to see how commercial both photography and painting can go in terms of serving corporate needs.

*Sigh.

What’s more interesting is how all these works can be read in multiple ways now. Many of the exploitation artworks originally glorify the men or companies which were taming nature. While this reading is still valid, that they’re now displayed under the heading “Exploitation” means we’re looking at them differently. What was originally optimistic is instead something we’re supposed to reflect on and think about how to change—both our actions with the landscape and our readings of corporate propaganda—moving forward.

Recreation and Tourism

It’s interesting that Recreation and Tourism is a distinct theme outside of exploitation. Not all of the exploitation of California’s resources is through using them up. Recreation and tourism is just as important a part of land management and just as important an industry to the state. Big trees. Big water. Big mountains. These are the landscapes which sell the California image as tourist destination for seeing and taking in and exploring nature.

These are also the landscapes that photographers and painters tend to consume and emulate the most. Where the exploitation artworks are clear what industry they’re depicting, many of the recreation ones end up pointing the finger back at the viewer and the artist and make me think about the fine line between how our desire to see and use these places both allows for their preservation as open space and risks degrading them through overuse.

East Bay

There’s also a gallery dedicated to East Bay landscapes. This is nice to see because it’s local—both the views and the artists—and while the exhibition is about California, it’s also always nice to see items of specific local interest included too. There are a lot of stereotypical nice landscapes on the East Bay but I prefer seeing the depictions of things we typically don’t think of as being picturesque.

Locals have a tendency to undervalue what’s interesting about where they live even while being triggered with intense senses of home from things that non-locals won’t ever understand. It’s those local-specific details which I enjoy seeing the most.

Now, on to the themes which were heavily biased in favor of a specific medium.

Pastoral

This section was all paintings* and pretty much all a nostalgic** view of California as an agricultural paradise. Not really a style of painting I like though it is interesting that there weren’t any photographs present. It’s not like photography can’t do the nostalgia thing.***

*Except for one Edward Weston photo. Oddly enough.

**Making the Weston inclusion even odder.

***Off the top of my head I’m thinking Pirkle Jones would be a good fit here. Or possibly Ken Light.

Between how we also react to old photos as inherently historic and nostalgic documents and how so much of the current trends in photography have been centered around faking and mimicking nostalgia as a reaction to the ubiquity of images and our loss of our lazy-man’s editor, there’s plenty of opportunity for photographs here.

All that said, I think there’s an element of nostalgia which requires things to be kind of made up. Photography, while not real, trades on reality in a way that paintings do not. Looking at nostalgic paintings comes with the understanding that things don’t actually look like that in real life. Looking at photos, especially landscape photos, still comes from a place where we expect the photo to be real.

Yes we should know better here.

Urban vs. wild

Meanwhile this theme was all photos, many of which were New Topographics type work. And while this made some sense to me since one of photography’s specialties is highlighting incongruent elements such as this urban vs wild theme, it’s not like people stopped painting or drawing the California suburbs.

And the urban vs. wild theme is in many ways about “California style” developments* which are meant to bring the outside in or incorporate controlled wilderness in the midst of suburbia. This isn’t an exclusive to photography thing at all.**

*Something that I wasn’t fully aware of until I moved East and saw homes listed as “California style” which look nothing like anything I’ve seen in California but instead feature more open floor plans and bigger windows and try to seem like they’re closer to nature.

**A lot of Hockney paintings (one of his joiners was in this gallery) seem to fit here. As does a lot of Bechtle.

Still, as with the nostalgia images, the difference in how we approach paintings compared to photos I think is a major reason why this gallery is photo-biased. The fact that the photos are “real” makes the incongruity more believable here.

Dystopia

This was also all photos. Which, didn’t surprise me at all. The dystopia photos, more than anything else here, are treated as evidence of landscapes taken to illogical extremes. You could create images like these in paintings but something about finding these in the wild makes the point better.* These photos are often wry and funny just as often as they’re sad. They’re also the images I liked the most in the exhibition.

*Sandow Birk’s drawings are pretty dystopian but even when referencing specific things, they’re pretty clearly made up.

Many of the dystopian photos revolve around land use and the weird juxtapositions between private and public. Looking through the rest of the galleries in this show, it’s clear how this idea is a constant issue in all the different themes and as such is really the dominant concept in the California landscape.

So many of the images here are about what we’re doing to the landscape. And who in particular is doing it. It’s up to us to see these images and ask the questions about whether we’re doing the right things or if the right people are doing them, and if not, what the right things are and who the right people should be.