Note: This originally posted on NJWV.

On Context

While Ai Weiwei wasn’t on my list of things to see at all, Pier 24 was at the top. I’ve been jonesing to go for years and just never managed to get my plans in order to get there. The current show features appropriated photos which, while something I’ve enjoyed intellectually in small doses, I was not sure I was ready for a full-on overload of.

I shouldn’t have worried. The space itself is awesome and the collection is more of a “physical version of a huge website”* in that is seems to have any photo series or print which you’d want to see from the canon.** It’s especially focused on photo series. Many of the rooms have at least one complete series of images. Since I’m used to seeing only one or two prints from each series in a museum, I loved being able to see the complete groups for a change. I can really get into what a specific photographer is doing, both from a sequence and a grouping point of view. It also assuaged a lot of my concerns as a context guy since Pier 24 is also known for its absence of context.

*A description someone much smarter than me came up with but which really captures the scope of the place.

**Comments about the demographics of the canon are best left for a different post.

Pier 24 doesn’t have wall text so you have to open up the exhibition guide to figure out what you’re actually looking at. The guide meanwhile only has super basic information—artist identification and a single project statement. As a result, a lot of people hold up Pier 24 to demonstrate how “only the image matters” or “context is irrelevant.” Inside Pier 24, I can see how that argument holds water. But that’s only because the space provides the context. Displaying the full series all together eliminates a lot of the descriptions that have to accompany a single image displayed by itself. Similarly, the way the different series on display interact with each other provides additional context.

Much of the appeal photography holds for me is in how it’s basically an exercise in recontextualization. As soon as you take a photo, you’ve taken it out of context by choosing what’s in, and out, of the frame. The way you choose to display or share the image after taking it is a new context.* There can be no true absence of context—although I would completely agree that context can be meaningless or unhelpful. In the case of this exhibition, since it’s about appropriated photos and recontextualization, the initial decontextualization serves the general theme.

*As can be the way the world changes after you’ve displayed the images.

The most interesting room in Pier 24 for this is the series of rooms of the Archive of Modern Conflict. These rooms are pretty dense with salon-style hangings of all kinds of photographs. Vernacular photos are mixed with art photos are mixed with functional photos resulting in all kind of new connections between images despite there being no context about the origins of each specific image.

At the same time, something about these rooms doesn’t hold up for me. Without any information, I found myself looking at the images with the half-awake, short-attention-span mindset I look at things on the web. If it doesn’t grab me right now, why bother looking? I wasn’t just missing the original context of the images, I wasn’t finding much compelling in the new context.

Which gets at the dangerous thing about buying into the no-context-needed mindset. Poorly-thought-out context invites short-attention-span consumption. This is easy enough to default to without any additional encouragement and, while a legitimate way of approaching a lot of media, is not something I like museums and other places that typically intend to encourage more thoughtful looking (or, at least, that’s why I go to them) to engage in.

Reappropriating vs Mining

Pier 24’s Secondhand was an interesting double bill with San José’s Postdate. Both shows used repurposed photos but where San José involved reclaiming images from a colonial past—demonstrating a very activist way of appropriating—Pier 24 is almost all within the same sort of western tradition and feels more concerned with the surface of images rather than what’s underneath them.

A lot of the work,* focuses on mining archives and extracting keepers—whether sequences, groups, or individual images—that look interesting to us today. It’s tempting to call this kind of thing “curation” only there’s no illumination provided.** They’re generally not about what the photo means and are instead going for the “oh this looks interesting” reaction. Other work*** involves doing clever things to photos to create new, interesting things to look at but which don’t didn’t make me rethink the actual photos themselves.

*Such as with The Archive of Modern Conflict and Erik Kessels (more on him later).

**One of my pet peeves is the way “curation” has become used on the web as a way of describing collections which, while often very tastefully selected, provide no information or educational information about what the point is.

***Most notably for me, Daniel Gordon and Maurizio Anzeri.

In both cases, the results can look pretty fun without really saying much. This isn’t a knock on what was on display, just that after having seen another exhibit which really investigated how powerful appropriation could be—especially in the context of colonialism and the representation of the powerless—I found myself wanting to see more work which explicitly examines the cultural context of the images, presents other meanings, and brings the appropriated images from the past into the present.

The only artist on the show who really did this was Hank Willis Thomas. His work in Pier 24—as well as his recent Unbranded work—looks at more than just how the photos look and instead focuses on the content of the photos and how our understanding of that content has changed over time. His work in the show was also particularly relevant given how Black Lives Matter has been constant over the past couple years. Viewing a lot of the older, recognizable but still-charged images through the flag frames suggests how these are commemorated and remembered as accomplishments rather than as part of an ongoing fight.

Erik Kessels & Vernacular Archives

Erik Kessels deserves specific comment since, not only does he appear to be the main attraction in the exhibition, much of his work critiques our concepts of vernacular photography and makes us think about how we use images.

One of the things that bugs me about a lot of current photography writing is its tendency to state that people did a good job organizing their photos in the past. From what I’ve seen looking at my friends’s and family’s photos is that staying on top of the photo albums was as rare and difficult to do then as keeping digital images organized now is. Even most people who did do a good job making albums have boxes of decades-old images that they haven’t gone through yet.

Managing and mining this archive—whether digital or physical—is a daunting task. What I like about Kessels is how he suggests other ways of using images than the pure documentary mindset that governs most archives of vernacular photos. In Almost Every Picture has a number of series that pull a common theme—a spouse, a pet, fingers covering the lens, carnival prizes—out of a larger cache of images. The archive doesn’t have to tell a story chronologically, it can have a completely different theme and the chronology will still be accessible. People age, fashions change, we can sense the passage of time despite the focus being something else.

As someone who’s still working through doing something with my photos, seeing alternative ways to approach my own archive is great to see.

Album Beauty meanwhile made me start thinking more about vernacular photos as common memory. While extracting specific series or groups of interest out of a vernacular archive is a nice skill to create fun sequences which tell small quirky stories, much of the appeal of vernacular photos is in their entire corpus and how they show us images that remind us of moments in our own lives.

This is something that Colors of Confinement touched on as well. Because so many Japanese internees have a gap in their family photos from the internment years, the photos that do exist from the camps work to remind them of their own experiences. It’s easy to say how photos erode memories by replacing them with whatever’s in the photograph, looking at other albums demonstrates how photos trigger memories as well.

Vernacular photographs,* describe a sense of place and time in a way that allows for our own memories of that period to be part of the experience. We flip through the contents of an album and pause when we see something that reminds us of our own experiences—a location we also visited, clothing or hairstyles that made us look awful, toys we played with or coveted. Ideally we’re looking through the album with someone else so the pause can become conversation as we share stories. But even if we’re on our own, the pause and remembering and slight smile in recognition will occur before we go back to looking.

*Though this is also something that the “snapshot esthetic” can do too. Blake Andrews’s review of The Family Acid is very relevant here.

And it doesn’t have to be an album. It could be a shoebox of prints or a carousel full of slides. Those are just as much fun to look through and, in some ways are a better shared experiences than an album is since it’s easier to pass individual prints or slides around.

Which brings me to 24 hours of Flickr. This room gets mentioned in every writeup I’ve seen on this show. It didn’t do much for me. It kind of feels like a physical statement about how awful the current deluge of photos is compared to how great the nicely-organized albums of the past were. Yes, people upload way more photos than they’d have printed in the past. And yes, 90% of those photos are crap. But there’s nothing gained by seeing how many 4″×6″ prints a days worth of uploads translates to.

What I took away from that room was how respectfully I treat photographic prints. In a room full of prints, all of which were treated as basically disposable trash, I still found myself trying not to step on any of them—even the brick-wall test shots half-covered in a low-resolution watermark.

Photographs as Byproduct

The rooms I liked best though contained photographs which were, essentially, byproducts of other ventures. Rather than being vernacular photos that people took to document their lives, these are things produced by government, big business, or a media company as part of an offered product or service. Some are intended as communication and illustration to accompany other information; some are merely an intermediate step of a production process; and others are artifacts that happen to feature photography but aren’t photos themselves.

The highlight is Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel’s Evidence. It’s one of the granddaddies of the field of appropriated photography and it’s awesome. Is it a bit superficial? Absolutely. But it’s funny and bizarre and simply a very well-selected sequence. I find it hard to believe it’s as old as it is since it still sets the bar for this kind of thing as an example for how decontextualization and recontextualization can work.

The photos in Evidence come from all sorts of governmental and industry archives. By themselves, in their original context, they would have been pretty boring, of interest to a small, specific audience—quite possibly boring to even that audience. Out of context and grouped together though makes these technically-competent photos anything but boring. Rather than wanting to know what’s going on, I found myself making up my own narratives and noticing things in the images that weren’t originally the main point—like the interactions between people in a group shot or the way a headless person is holding the intended subject of the image.

I also really liked Viktoria Binschtok’s work investigating the locations of Google Street View (GSV)photos. There have been a lot of GSV projects but I really like the idea of not just rephotographing the street view image but going inside and making the automated, corporate image into a real place. GSV in many ways demonstrates everything that makes for bad photography. It’s automated and distant and unedited and presents an unnatural point of view. But these are also what make it so compelling to play with. There is no existing editorial voice to contend with and you can sit down, dig though as much of the archive as you can handle, and do whatever you want with the results.

Most of the projects though have been either commentaries of GSV itself or attempted to find street view images that looked like “real”* photographs. Binschtok though uses GSV as just the jumping off point to play with the concept of intent. Her photographs paired with the GSV imagery produce a result that makes both much more interesting. It reminds me a little of rephotographing Stephen Shore with GSV but rather than starting with the interesting, fully-intended image and showing how bland the location looks on Google, these start with the bland GSV images and force us to see how they can be transformed by looking with intent instead.

*Read, images that look like the accepted canon of “good” photography. This is also an idea that deserves a post all of its own.

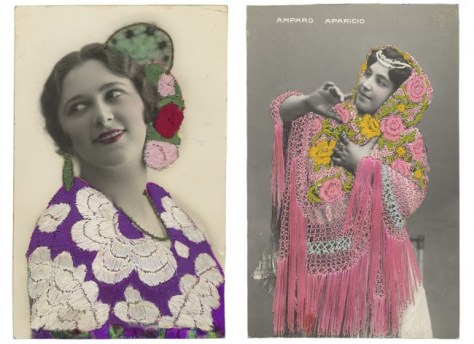

The collections of photos that have been prepared for halftoning and printing are fascinating.* These are byproducts of the printing process. They’re not the original negatives nor are they the final halftoned prints. Instead they’re photographs which have been painted and marked up to improve the contrast and eliminated unwanted details so that they will reproduce well after offset printing.

*Especially given my background in printing. I’ve worked as a prepress operator at an offset printing shop as well as an OEM support lead for digital printing and so have lived the “how to go from paste-up (or digital file) to printed page” life for over a decade.

This is the kind of thing that would be called cheating today so it’s instructive to see how much manipulation was required in order to get a usable final image. None of these photos are lying even though they’re all faked. It’s also a reminder of how much image processing is always needed behind the scenes in order to make a decent photographic print.

Outside of being a reminder of how photographs end up on paper, these objects are also wonderful commentaries on photography as an exercise in recontextualization. They’re not just extracting what’s in the photo from what’s outside it, they’re also painting out details and reframing what’s in the photo as well—in-game action photos become posed studio images, group photos become headshots. And then they’re put on the wall of a museum where we no longer know who the players are you see what an editor selected decades ago as the most-important part of these images.

Finally, there are photos which are used as the substrate for other products. The embroidered postcards are beautiful objects and the ID badges are great fun to look at. In neither case am I really looking at the photos though. I’m seeing them as objects and remnants of a specific period of time. I appreciate seeing multiple specimens—Pier 24’s scale does most of the heavy lifting here—as I can get a better sense of the craft and usage of the pieces.

It’s no surprise that my favorite pieces at Pier 24 were these byproduct photos. They were useful objects which we can relate to—even after their previous functions are no longer needed or remembered, we recognize enough about how they were used. Recontextualizing them into a museum allows us to relate to them as useful objects and appreciate the new context along with the original craft. Looking at photography—or really anything else in a museum—needs to be more than just an academic surface-level exercise for me. I need to see what the photos are doing, how they’re being used, or what statement they’re making.