Note: This originally posted on NJWV.

Toys are intriguing, and I want to see what I can do with them. On a deeper level, they represent one way that society socializes its young.

I had a chance a few weeks ago to check out David Levinthal at the San José Museum of Art. It’s worth seeing. While at one level, photographs of toys can feel like something which falls into the clever gimmick side of things.* These are not just photos of toys—in fact, there’s nothing juvenile about anything here.

*Especially in our upworthy-saturated age where this exhibition just felt like something that could be titled “Common toys photographed as if they were real, you won’t believe the results!”

A lot of times, Levinthal directly apes existing photographers or photographic work. Just as often though, he starts off aping something specific and proceeds to get sidetracked into deeper investigations into the nature of the toy itself—and what the toy represents in our socialization. In both cases, the results retain hints of the toyness but also take us beyond into realms were we start rethinking how we perceive and react to the subjects of photos in general.

There’s a lot of cultural baggage present. In the subjects, in ourselves, and in how we approach and react to the medium of photography.

Even though we know—or should know—better, it’s so easy to fall into the trap of thinking that photography is true and that certain manipulations of the subject are somehow unethical. Maybe it’s photographic cheating. Maybe it’s more along the lines of the current market for unretouched photos—typically of women—which is either about shaming celebrities for “lying,” embarrassing them for being real, or setting a “good example” for our girls.*

*I’ll admit that I don’t understand the gotcha nature of these photos and I’ve never understood exactly what the intended message accompanying their release is.

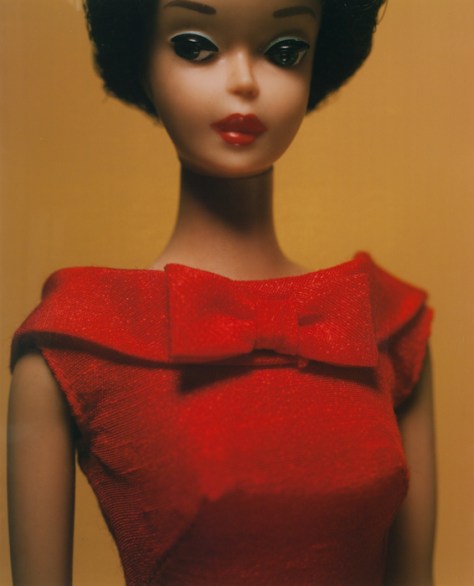

For me, Levinthal’s photos of Barbie do a lot more at calling out the artifice in photography—especially fashion photography—than any of the supposed ethical violations. By photographing Barbie in the style of Irving Penn and Richard Avedon, we can see how artificial everything really is. The images read as fashion—heck we’re looking at the clothes more than we do in most fashion photos where we can be distracted by the charisma of the model. At the same time, we know none of it is real and can start asking questions about lighting and makeup and color and depth of field and focus and what message this kind of toy sends to our kids.

Light and focus in particular are two tools which get a lot of extra attention in this show. Many of the photos are intentionally out of focus—emphasizing form over details. This makes it easy to lose track of the fact that these are toys so we start filling in our own details. When things are theatrically lit on top of this, I found myself reacting to these as if they were real even though I knew they weren’t.

But not in an uncanny valley way. The lighting and focus tricks manage to avoid both the valley and any sense of hyperreality. We see mood and gesture and more adult natures in the toys instead.

Levinthal is troubled by the proliferation of porn and sexuality, especially when it becomes embedded in toys and child socialization. I can see his point while also finding it kind of quaint; art museums tend to skew in the complete opposite direction.

His approach with the dolls manages to point a lot of this out without being either skeevy or crackpot. He’s not being a creep with kids’ toys nor is he looking for things which aren’t there. He’s mining all these toys for their mythic imagery and pulling out all kinds of things that kids just absorb.

They’re never just toys. Kids play with toys to roleplay and figure out their reality. When toys get pushed into situations beyond the orthodox use cases,* a lot of this latent imagery becomes more apparent.

*As someone who fully agrees with Micheal Chabon’s rant about the orthodoxy of Toy Story, I sure hope they do.

So many of Levinthal’s series are about mining specific myth families. Whether they’re famous baseball moments or the Wild West or iconic historic moments (e.g. Little Bighorn, Iwo Jima, and The Alamo), in all cases the toys become larger than life. They’re gateways into movies and fantasies and learning what it means to be American.

Many of them speak to me and my youth and remind me both of being a kid again and what I get to see my own sons play with. The nostalgia though is tempered with warnings about how almost all this imagery is, or can be, problematic. These are all myths from a simpler time. We know better about them now.

Nowhere is this more clear than in the blackface photos. Where most of Levinthal’s work is subtle and allows us to imagine things as being real, these photos are in-your-face grotesque. They emphasize how these can’t be fun no matter how “harmless” people claim them to be. This isn’t a fantasy myth, it’s a dash of cold water on top of what used to be common imagery.

This is quite a different approach to this subject than Carrie Mae Weems’s subtlety. It’s no less powerful and very interesting to compare American Icons with Levinthal. The subtext of common household toy is the same. Weems shows how insidiously common they could be. Levinthal forces us to really observe the nastiness of the stereotype.

The photos of Nazi toys are similarly troubling. In this case, the toys aren’t grotesque; they’re seductively beautiful. By being toys, we can kind of explore this seduction in a safe space. At the same time, even blurred, these photos remind us how much we’ve been socialized. Holy crap is an out of focus Hitler doll still pretty fucking menacing.

From a design impact point of view, the Nazis knew exactly what they were doing. It’s clear in the photos how much Levinthal was drawn to the designs too. From a kid’s point of view, it’s also an important lesson on making sure that we adequately explain how we can be seduced by things that are bad for us. And that it’s okay to feel that and even acknowledge the compulsion without having to act on it.

It’s especially interesting to compare the Nazi photos with the photos from Hitler Moves East. In this case, Levinthal isn’t mining the myths as much as he’s staging and creating his own. Since there are few photos of Operation Barbarossa, the result is almost a graphic novel illustrated with Capa-like photos of toys.

Just like a graphic novel can pack serious punches when softened with the appearance of kids-stuff, these photos illustrate material which may have been too heavy to handle if actual photos existed.

I haven’t seen a photo exhibition like this which made me truly question how real every image was or to what explicit portion of the image I was reacting to, or whether my reaction was a product of my socialization. I was second guessing myself a lot. In the best way. With a lot of questions I should ask myself about all photographs I encounter.

Also:

Most of the prints on display are large-format Polaroids. I’m not going to go into tech geekery here. It’s just wonderful to see them in person.