Purely coincidentally, I also recently went to see Secondhand at Pier 24. My thoughts about it are fewer and less interesting than @vossbrink’s, so I’ll try to express them with some brevity.

Pier 24

I *always* feel out of place in an art museum. Always.

— Nick (@kukkurovaca) May 4, 2015

Pier 24 is weird. I’m not big on museums and galleries generally, and this was perhaps my least favorite experience in one, because it is one of the least accessible contexts I’ve encountered for viewing art.

To start with, it is only open during weekday working hours, and by appointment. It’s free, which is nice, but it is essentially never accessible to someone with a regular work week. That speaks volumes to who it (isn’t) for, and is one of the major reasons why I hadn’t visited previously.

The “no text on the walls” gimmick is ::shrug:: for me. I’m sure there’s an argument to be made for letting work speak for itself, but I’m not the one to make it. (And if you make it to me, it’ll probably sound like the voices of the adults in Charlie Brown.) Public-facing displays of art should include as much useful context as is feasible. This is my stance regardless of whether the work in question is something I happen to know a decent bit about or not.1

That said, the information in the book is adequate. I don’t think I gained anything from reading it in a book rather than looking at it on the wall. Mainly it just induced unnecessary cognitive dissonance to navigate a relatively non-linear space while flipping through an extremely linear book.

Kessels

At Pier 24 for the first time. So much clever art and so cleverly presented.

— Nick (@kukkurovaca) April 27, 2015

Erik Kessels seemed to be What It Was About, with other artists rounding things out a bit, and in some cases (the Richard Prince cowboy) seeming actually a bit out of place and gratuitous.

The Kessels stuff seemed to be largely about playing with scale. Expanding and exploding. Or reducing and inundating. The result is very clever.2 I was repeatedly put in mind of those Stephen Biesty cross-section books, not because Kessel’s explosions are illustrative, but because they look like something that has been chopped up into pieces.

That being said, I did think the big Photo Cubes were pretty funny.

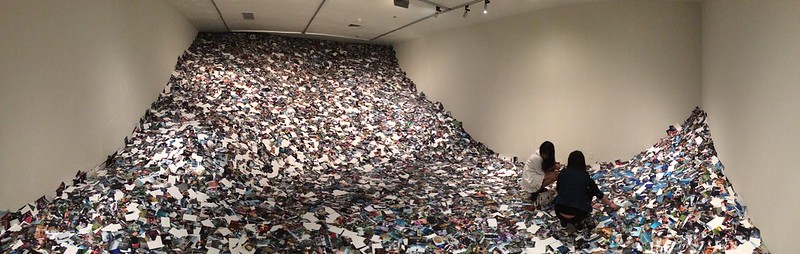

The Big Fucking Roomful of 4×6 Prints3 was also entertaining, mostly just because it was fun to watch people get down into the piles and investigate them under the supervision of a bored-looking docent. I also found myself for the first time actually appreciating watermarks on photos, because they provided a layer of information about the image’s source that was otherwise missing.4

I wasn’t taken with Kessels’s provided explanation of the room’s purpose:

I visualize the feeling of drowning in representations of other peoples’ experiences.

Not to rehash The 1978 Test, but what is the mindset of the artist for whom an image glut is a problem or source of fear and anxiety? Why does or should an abundance of imagery induce a feeling of drowning?

A whole world full of other people and their experiences was always there before. And unless artists are all thoroughgoing solipsists, they must know that. So why is the representation of those experiences perceived as overwhelming? Why does the artist (and why is the viewer expected to) “drown” in it? Why can I not escape the feeling that the so-called vernacular image can only manifest to artists and curators as a problem to be solved or an opportunity to exploited? Is the place of an artist in the world dependent on the anonymity and invisibility of everyone else in it?

I sometimes think that at heart, the “serious” photographer has never really evolved past the original form of the camera operator: a person whose vocation is defined primarily by access to a novel technology which for their audience is still unavailable or mysterious. The photographer as gadgeteer has generally been scorned by those who pursued the medium as an art, but maybe that was always just a case of Protesting Too Much. And maybe, deep down, this secret shame has been driving art photography all along.

Or maybe not. But it’s one way to account for the persistent down-the-decades anxiety of the photographic artist confronted with a world of vernacular images.

Archive of Modern Conflict

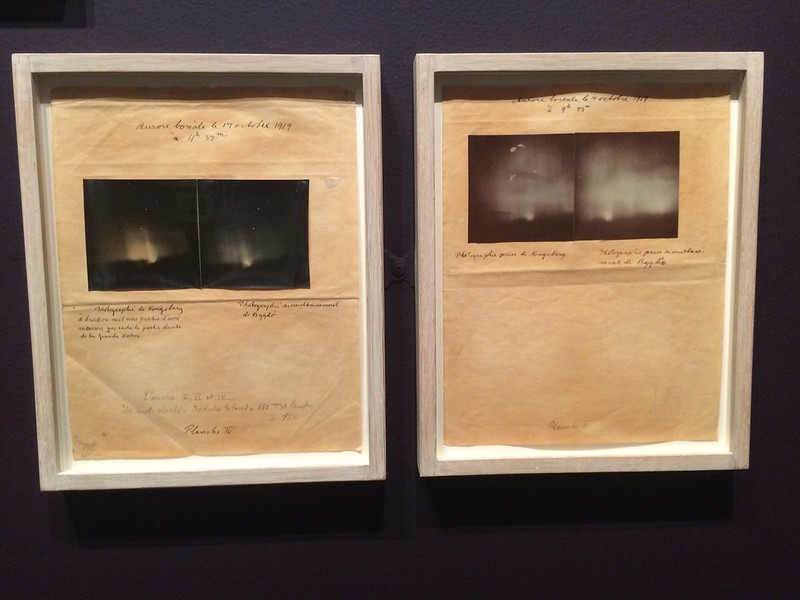

Some of my favorite photographs were from the Archive of Modern Conflict—but as a series, it was not so great. Although I cannot find the tweet at the moment, I think @vossbrink put it as the whole being less than the sum of its parts. This, and a few of the other rooms as well, put me in mind of Szarkowski’s statement that

It is important to remember that an anonymous photographer is simply a photographer whose name we have lost, perhaps temporarily. When we recover it, and find out the name of his town and his wife (or her husband), we can begin writing dissertations about him or her, but the work has not changed.

This is, I suppose, a rather old-fashioned way to look at vernacular photographs. But more often than not, what I feel when I am looking at some photograph that has been appropriated into a sequence or other larger work is that really, I would rather know more about the person who made the photograph and less about the what the appropriating artist has decided it should now come to mean.

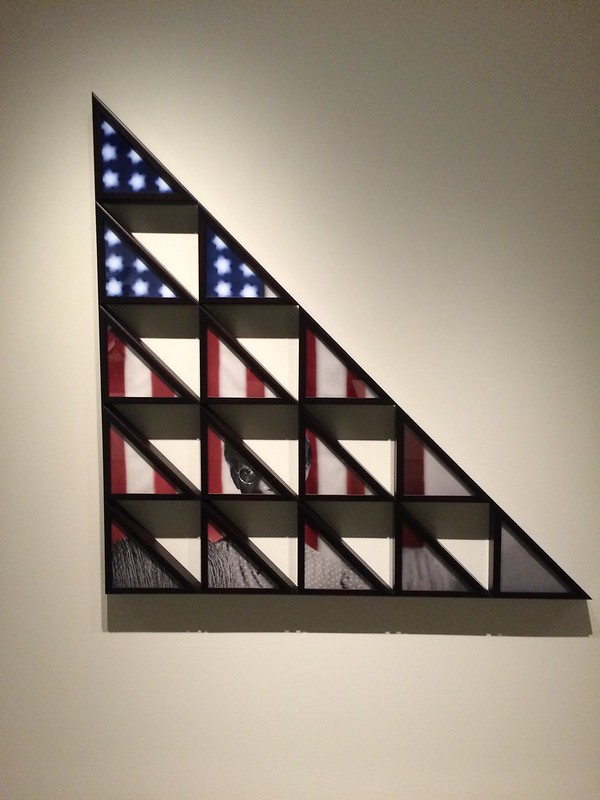

Hank Willis Thomas

One part of the whole experience that I really, really liked were Hank Willis Thomas’s flag presentation case…I’m not sure how to describe them except as photo tangrams, really. I don’t have anything illuminating to say about them, but they’re great.

And no, I didn’t just like them because I have a thing for flags. Although man, did I kick myself for not bringing my IR camera that day.

Appropriating Down

Something that @vossbrink and I have been talking about lately has been the difference between “appropriating up” and “appropriating down,” in the sense of “punching up” versus “punching down” in comedy.

This useful distinction has seen a lot of action over the last few years in discussions of comedy, and specifically who is or should be fair game as the butt of a joke. Basically, “punching up” means comedy that cuts at someone with more power than you, and “punching down” means comedy that cuts at someone with less power than you. Most non-assholes would agree that it makes more sense to look at edgy comedy this way than according to the rubric that everybody is fair game or that a comedian can be an “equal opportunity offender,” because of course the world is not a fair or equal one. Punching down is the comedic equivalent of bullying.5

Recently, and particularly in the context of discussion of Prince’s Instagram stuff, where—ethics & legality of re-use/copyright stuff notwithstanding—we’ve been thinking about appropriation in those “punch up”/”punch down” terms.

Wow men don't even need to be part of the process to make money off women's bodies in art anymore, how groundbreaking http://t.co/eT9wL9mzcK

— Kasia Mychajlowycz (@xokasia) May 26, 2015

That's a good tweet, but the actual wapo post is sort of headscratch inducing for me, b/c it's not like Prince just started doing this

— Nick (@kukkurovaca) May 26, 2015

Nor is that practice at all specific to Instagram or online photos.

— Nick (@kukkurovaca) May 26, 2015

I don't really have strong feelings about the ethics of it, but I find Prince's stuff to be megasnooze.

— Nick (@kukkurovaca) May 26, 2015

And in general, artists appropriating vernacular images rarely fails to bore me. Appropriate up, not down.

— Nick (@kukkurovaca) May 26, 2015

@kukkurovaca There's a consent/punching down thing about his recent work that bugs me.

— nick (@vossbrink) May 26, 2015

@kukkurovaca HAHAHA. Jinx.

— nick (@vossbrink) May 26, 2015

There’s a pretty big difference between the kind and quality of commentary and criticism we find in Prince’s use of Marlboro ad images and what we find in his use of images from Instagram. And thus a difference in the worth of those bodies of work.

I mentioned above that Prince’s cowboy is out of place in Secondhand; it’s because the majority of the show consists of work that appropriates down. I think there is no question that it is exploitive of photography produced by regular human beings—the most charitable question I can think to pose is whether it is merely exploitive in the sense of the exploitation of a natural resource. Conversely, many of the best works in Secondhand are the exceptions to this rule, the images that appropriate up by drawing on iconic historical images or imagery produced by governments or institutions.

- Granted, outside of the particular areas of photography that I’m very into, usually that’s “or not.” ↩

- As you may already know, I generally use “clever” in a derogatory sense; this is not an exception. ↩

- Not the actual title. ↩

- “A work of art so bad it made me reconsider my feelings about watermarks on digital photos” is a very mean sentence that I decided to put in a footnote instead of the body of the post. ↩

- Note: The meaning of the word “bullying” has been muddled somewhat recently, especially as regards online debates, especially by being used as a slur against legitimate criticism from women of color. I mean actual bullying as such, in which someone uses their size/power/money/etc. to go after someone with less size/power/money/etc. ↩